(Click icon to download PDF...)

Craft journal, vol. 39, no. 151, issue 1 for 2019.

Text by Kjersti Solbakken

Upholstered Care in Monochrome Metres of Cloth

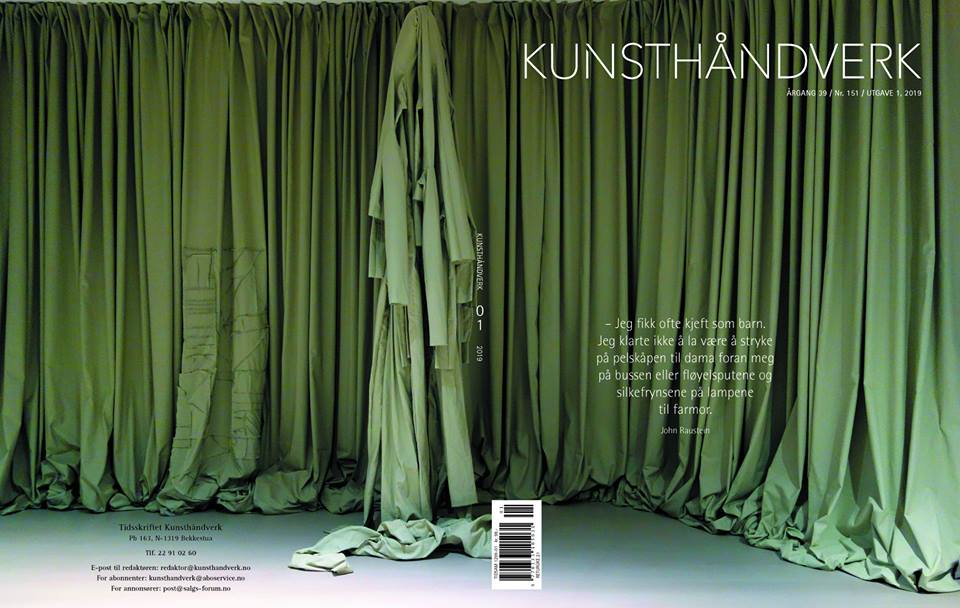

Something happens to the room every time John Raustein occupies it. He upholsters the architecture, drapes all the walls and reduces acoustic vibration. The surroundings are calmed down to the point where you might feel smothered. Textile pictures and forms gradually emerge. It feels like a clammy hug, like exhaling a bit too late, or that picture on your retina you can't get rid of. In his extensive exhibition trilogies, he sews, stitch by stitch, through a world which language fails to describe.

It's September 2018. Elections are taking place in Sweden, and the right-wing populist Swedish Democrats seem to be doing well. I myself am in Trondheim, more specifically, at the contemporary art centre Trøndelag senter for samtidskunst, where John Raustein's exhibition Away from the Window and Into the Light is being held. John sits next to me and talks about what it's like to be a homosexual in Chechnya. He talks about rendering something or someone invisible, about privileges and resistance, and about fencing oneself in with a barberry hedge. Later in the evening, on www.hekkplanterdirekte.no, I read that barberry shrubs are good for protecting property: the thorns scare off thieves.

"I'm interested in how current events take us back in time and space. It's about suddenly remembering something you didn't know you'd forgotten", says Raustein.

The white walls are gone and we're surrounded by dry, matt, cotton fabric of the cheapest sort. Monochrome works in exhibitions hold to a limited palette: dark blue, a dirty mint green or a dusty light grey are all you get. And already here, a sense of longing emerges. A longing for what? Pink? Contrasts? Sharp edges? This absence of an indeterminate 'something' is a feeling that is patently present in Raustein's large textile installations. The absence even manifests itself absolutely concretely, physically, through works with inset hollow shapes. It's not until you take the time to really be inside the work that it gradually conjures itself. A staged architecture emerges, which reminds you of an edited memory.

Raustein always alternates between leading and leading astray. In the exhibition's title, he asks us to move away from the window and into the light, but the room is full of shadows.

"It's about the feeling of being a child who's told that he's blocking the light", says the artist.

In the list of works, a number of titles are listed, but I myself must draw connections between the titles and the works around me. There are no numbers and no map. I catch myself hunting for Invisible Fences. I search for Waves at Night and The Black Hole, and end up accepting that all the works carry all the titles.

Swans stiffened with sugar

Raustein's interest in textiles is closely connected to themes such as identity, rendering something invisible, and being an outsider. These all relate to his own background, to growing up in a foster home and eventually living as a young homosexual in the midst of Norway's Bible Belt. One memory about an absolutely special room has become an important spring board for his artistic practice today. When he was very young, almost every Wednesday, he attended what he calls the Aunts' Club.

"These aunts were guardians for my mother and her twin sister, who had lost their parents at an early age. Their follow-up took place through the association of aunts. I didn't go to kindergarten, so I went to the Aunts' Club too", Raustein explains. "Aunt Bergit was an expert at Hardanger embroidery, Aunt Kirsten was a virtuoso at tatting, and Ada—she smoked like a chimney and crocheted the most fantastic swans. After completing one, she would stiffen it with sugar water. I was too little to learn the techniques, so I often sat under the table and played and listened while the aunts chatted and worked."

Raustein tells me that the position of textile art is a driving force in his work. For his upcoming exhibition at Kunstnerforbundet, he has worked site-specifically with the gallery's skylight room and its historical status as the room most often devoted to painting.

"I'm fascinated by how textile works hung on top of textiles are perceived as invisible, especially when they're the same colour. They merge with the wall. In this way, I create an image of the invisible work in textile art throughout history."

Invisible structures are dealt with in Raustein's artistic practice, not merely thematically but also through his material choices. The edge of a woven textile is called the selvedge. It's often woven much more tightly than the rest of the fabric and makes the metres of cloth stable during the production process. The selvedge is often cut away before the fabric is sewn, otherwise problems may arise down-line. In Raustein's universe, the selvedge itself is the starting point for several works. Through his care for the sensory aspects of a textile, he conjures tactile memories in the viewer, whether they are memories of crepe bedclothes, stiff shirt collars, dirty rags, a bean bag, or the identity banner for a marching band.

"I was often criticized as a child. I couldn't refrain from stroking the fur coat of a woman in front of me on a buss, or the velvet pillows and silk fringe on my grandmother's lamps", he admits.

Rag rugs and connotations

It's January 2019, and in Raustein's studio at Frysja in Oslo, I see a large green rag rug hanging on a wall. He tells me the light can't get in. The skylight is covered with a thick layer of snow. Nevertheless, thick foliage fills the room. On closer inspection, I see that the rag rug isn't made in the same way as are most rag rugs. Thousands of sewn-together flaps in cotton fabric create a picture of a rag rug, or rather, the feeling of a rag rug.

"I wanted to recreate the experience that many people have had of lying on the floor on a carpet and playing, regardless of whether you think of a rag rug or a Persian carpet."

And it's precisely this approach that characterizes Raustein's works. The things that are closest to us, which all of us carry, are, in Raustein's works, monumental, but never spectacular.

"I try to peel away in order to make it easier to associate. This may cause poor choices to be more consequential, since one is then forced to move even closer to what is essential, but hopefully, it also makes it possible to create an even larger room to enter into."

Raustein is interested in the relation between textile art and architecture. He talks about textiles that have decorative functions, absorb acoustic effects, and which mark a boundary between open rooms and luminous windows. His textile installations alternate between erasing and emphasizing architectural elements. The dirty mint-green colour, found on metre-upon-metre of stacked cloth in his studio, was his mother's favourite colour. The same colour also marked large parts of Oslo in the period after 22 July, through the panels that replaced broken windows throughout the whole city. Furthermore, the colour is often associated with care-giving institutions and waiting rooms, and in many ways feels like a 'public' or 'municipal' colour—whatever that might mean. In Raustein's works, it's as if the matt-green cotton sucks up contemporary connotations and associations from the environment, whether they're super-local or bordering on something private, or they come about through a push notice on your smart phone.

"I don't want to use used textiles because there are already too many connotations there", he says. "The cotton cloth is cheap and comes on a roll. It allows me to bypass some stages of the creation process so I can get right down to the core of the work."

Raustein's practice is marked by extensive self-imposed work with time-consuming, repetitive techniques in monotone materials. He calls the work process a manifestation of time.

"'Stick to the plan' has become a motto. There's no room for creativity in that part of the process. When people talk about time, it's often a sensation. For me, it's about finishing the work."

When everything falls into place

Raustein's upcoming exhibition at Kunstnerforbundet in April 2019 marks the end of a trilogy he's worked with for a three-year period.

"Working with trilogies lets me prolong an artistic thought process without necessarily feeling I need to do something completely new in each exhibition. The exhibition's title will be When Everything Falls into Place (Når alt faller på plass). The title can seem hopeful and uplifting, but it also bears witness of a potential catastrophe", says Raustein. "When everything falls into place. It happens in a mere second. What happens the next second? Maybe the title's encouraging, but at the same time, it provokes alarm. When everything falls into place, that's actually the end."

John Raustein's ongoing exhibition trilogy started with the exhibition While you Become Dust (mens du blir til jord) at the gallery KRAFT- rom for kunsthåndverk in Bergen in 2017, and continued with the exhibition Away from the Window and Into the Light (Bort fra vinduet og inn i lyset) at the contemporary art centre Trøndelag senter for samtidskunst in 2018. The trilogy ends with the exhibition When Everything Falls into Place (Når alt faller på plass) at Kunstnerforbundet in Oslo.

This text was first published in Norwegian in the craft journal Tidsskriftet Kunsthåndverk, vol. 39, no. 151, issue 1 for 2019.

Translation, Arlyne Moi