(Click icon to download PDF...)

Essay by Tommy Olsson

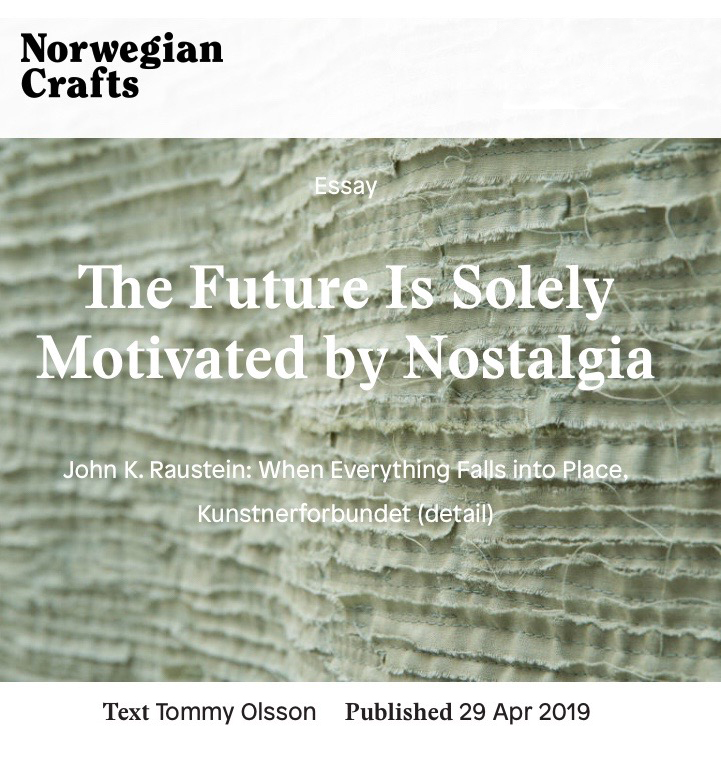

The Future Is Solely Motivated by Nostalgia

Artist and critic Tommy Olsson reflects upon John K. Raustein's exhibition 'When Everything Falls into Place' at Kunstnerforbundet in Oslo

Pick a colour. For example, green. But not just any green; choose one with conflicting associations. A green you can almost only describe by pointing to something else. Chrome-oxide green, but not quite. Hospital-corridor green, but only approximately. American execution-table green, but just barely. Pistachio green, but a bit too dull. Mint green, but a tad unpalatable. A difficult green; cold, subdued, and non-organic. An industrial green. The colour painted on water cisterns and aircraft carriers, to protect them from weather and wind. The green you find on a shirt in your closet that you immediately forgot about after you got for Christmas along with two other shirts, one red and one blue, that someone in your family bought on sale, in a panic the day before Christmas Eve – three shirts for the price of two.

Pick a medium. Textile. Lots of it. In the same colour – the one I tried just now to pinpoint without getting more than an approximation. And there's something about just that. The largest room at the gallery Kunstnerforbundet in Oslo is completely draped in this colour, so it seems likely that it isn't randomly chosen. Or that the installation is a labyrinth – which it was last time I came across Raustein's work when he exhibited at Galleri Format in Oslo, and in a similar way, took over the

whole room in order to conjure a parallel universe. But back then the installation was brown, and there were variations in the colour tone. If I remember correctly, there were a few passages of pure black and blue (but my memory might be off). In this new exhibition there's no variation at all. The same nuance of green tyrannically reigns supreme. So maybe it's not a labyrinth that poses any direct challenge to our sense of orientation – the room is too small for that anyway – but the ceiling is high enough, so you could get the intended dizziness when you look up as you enter the room and everything you see is green. Not because you can't find the exit, but because at that moment, you don't exactly see it, and because the rest of the world – the way you remember it – is no longer within reach. And then it happens: the idea hits you that the pharmaceutically green drapery could potentially expand into infinity, and the feeling that you may never again see red and yellow. It's not exactly intended, but When Everything Falls into Place falls mostly into place as part of a larger map, or a larger labyrinth, and – since it's too tempting for me not to say it – a disturbing green becomes an upgraded version of installation art such as we remember it from when we were young. Back then, to walk into something like this had the same smashing effect of fearful pleasure as it does now, but it was much more intense. And of course, this will work as it should on those who are children today, even though no screaming children are running around in ecstasy when 'yours truly' stumbles around in the room and thinks his thoughts.

To walk into something distinctly other, out of the everyday and into the unknown, is probably a psychological necessity in a somewhat organized society, and something I would imagine everyone does regularly in one way or another – whether it's porno, football or narcotics you resort to. It's of course only speculation on my part; when your occupation is to write about art, this need is formulated from the other end of the room, and I've tried for many years to achieve something resembling an ordinary life – but despite that, I move in the same large labyrinth as everyone else. And I think the need to move into something else, something different, is universal.

'The labyrinth' is also a concept that was used when I turned 40, when people with common interests started falling away. 'The labyrinth' was early on an umbrella term used to describe the different archival systems for the mass of literature, film and music that a deceased acquaintance had collected since youth, and which the individual now, by exiting this life, had left to those who were closest, who were now trying to organize and do something with it all. The bereaved partner and/or closest family usually need help from the deceased's almost-as-nerdy friends to get any overview whatsoever. A project of sorting, mainly, but with your own sorrow and memory as compass. But I promise: even though you have solid knowledge of first editions of obscure poetry collections and the market value of a rare punk single, this is usually a matter of a huge amount, with an at-best apparent organization based on the deceased's own overview and personal priorities. Regardless of whether it was a married man with children, or a guy who lived alone (there are women who leave behind huge collections too, but they're usually more organized – the books are shelved alphabetically by author, the records are organized according to genre, etc.), it's always seriously labyrinthine in form.

I know this is a digression here, and potentially only fully graspable for a handful of men around my age, but there's a deep resonance in all this green. Because of course it's not just a pile of textiles hanging on the walls and from the ceiling. When Everything Falls into Place is filled to overflowing with different objects and signals, all in the same colour, and all in the same material. Pillows in different formats, often long and thin, connected by a series of knots – almost like that drawer filled with electrical cords that everyone has somewhere, with plugs for electronic gadgets that became extinct in the 1990s, but which you resolutely take along to each new place you move to, because you never know if you'll need one. But here you also see what you immediately perceive as pictures on a wall; appliqués of checked patterns in frames. Of course, like everything else, consistently in the same green textile.

This strategy, as mentioned, also existed in the mainly brown installation from a few years back, and there's a little media-specific punchline in this translation of a painting on a wall into textile appliqué on textile. It already functioned superbly the first time, but its expression becomes even more salient when it also becomes a monochrome hung on a monochrome, in a situation where you need to look repeatedly at your own hands to check that you yourself haven't turned metallic green along the way. It addresses a larger conversation, and it also leads directly back to the title: When Everything Falls into Place. What is it, exactly, that falls into place? When I, for what eventually has become many years ago, noted a distinctly contemporary nerve in Norwegian textile art – before I was sufficiently able to realize that this nerve could be found in works that in some cases were made a very long time ago, and which didn't necessarily begin to exist the moment I discovered it – it (the nerve) had to do with two main tracks, under one stigma. All this is still present, even though the stigma has now reversed to broad acceptance, and not a small degree of hipness.

The one track was, and is, works in textile that either incorporate other materials and techniques, or which interact with other materials and techniques. For example, as intimated in this installation and in the foregoing: painting. This is probably the most common occurrence, and with such a long tradition that it has become a basic aspect of textile art. The close proximity of tapestry and painting is beyond question. There have been discussions about whether the tapestries of Hannah Ryggen actually in some sense should be understood as paintings, and this isn't an isolated example. But there are also many examples of the use of printing techniques and three-dimensional works, and – as here – installations, even though it's more difficult to find cases of works dating back further than 1960. Sometimes it seems like textile art is capable of annexing everything in its environment, and of exposing a potential that can cause a tired critic to say things like 'this is the new video'.

The other track is the kind of textile art that makes a point of not pretending to be anything other than textile, and which balances across the abyss of associated conventions: curtains, drapes, and, not least, clothing and direct contact with the body, which would otherwise be naked. John Raustein does something truly hefty by combining all this, and it could surely be done in a far smaller format, but I doubt anyone would have noticed it.

Even while standing inside all this, there's something I didn't reflect over until now, afterwards, because I'm sitting and writing. Because sometimes it doesn't seem accidental that 'text' is the first four letters in 'textile'; things would be very different if I didn't produce text, but far more challenging if I didn't use textiles. I'm not the sort of person who wants to bar others from all the possible readings and interpretations a title offers when it's the kind that requires entering into dialogue with it, but I think these things are some of what, ideally, should fall into place. But I wouldn't, for that reason, say it actually happens – and for all I know, the title could have originated far from the field of textile art, from a hunch the artist had about something completely different. But even so, it's what I would call a good title, since it can be applied to several contexts. Most people will read it with a degree of expectation, because it's this 'When' in the title that points to something that hasn't yet happened. It hasn't yet fallen into place, but when it does, you're damn well gonna see it. As a logical progression in the species' development – humans originally perceived the world in black and white, before the intensity of red could no longer be ignored – one can think of this green colour, which I'm quite sure some viewers will see as grey, as quite a new discovery. But the day everything really falls into place, this 'grey' will have become a past evolutionary stage. And we will remember all that is new long before it happens.

Tommy Olsson